If you want to turn a vacant lot in your neighborhood into a community garden, the Philadelphia Housing Development Corp. is here to help. The quasi-municipal agency that manages the sale of city-owned property has long been criticized for letting thousands of city-owned vacant lots languish in limbo, blighting neighborhoods citywide. But this summer, the PHDC set up a new website to facilitate the process of putting vacant lots to productive use, including community gardens. If you have spotted a vacant lot and want to acquire it to turn it into a community garden:

If you want to turn a vacant lot in your neighborhood into a community garden, the Philadelphia Housing Development Corp. is here to help. The quasi-municipal agency that manages the sale of city-owned property has long been criticized for letting thousands of city-owned vacant lots languish in limbo, blighting neighborhoods citywide. But this summer, the PHDC set up a new website to facilitate the process of putting vacant lots to productive use, including community gardens. If you have spotted a vacant lot and want to acquire it to turn it into a community garden:

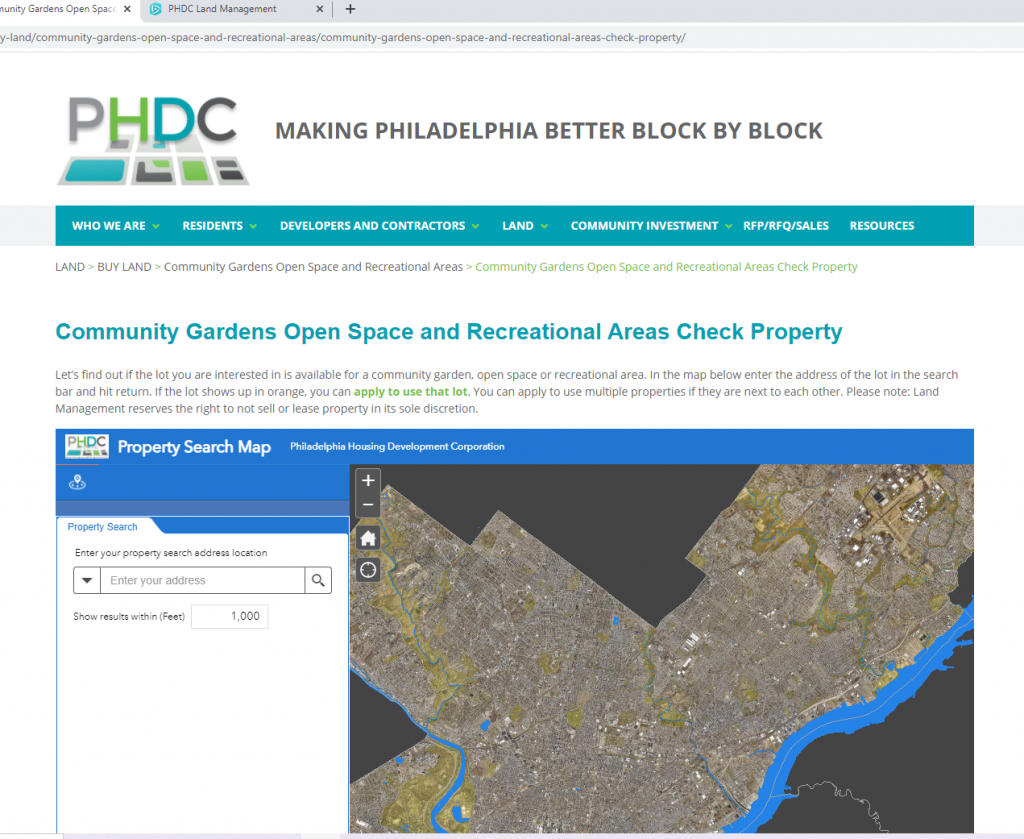

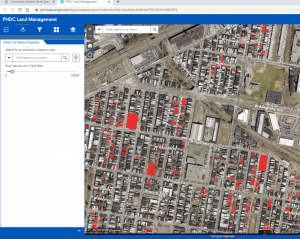

- First, peruse this map to see if the lot is city-owned and available.

- Next find out if you’re eligible to purchase the lot and submit an application. You’re supposed to get some response from PHDC within 120 days.

PHDC’s overhaul of the system for selling publicly owned vacant lots is a result of a reform process that has been underway for several years. The push for a better way was spurred by reporting by Plan Philly and WHYY, the public radio station, which uncovered a backlog of more than 18,000 “expressions of interest” to buy some of the more than 8,000 vacant lots in the city’s inventory. Many of the queries had gone unanwered for years.

PHDC’s overhaul of the system for selling publicly owned vacant lots is a result of a reform process that has been underway for several years. The push for a better way was spurred by reporting by Plan Philly and WHYY, the public radio station, which uncovered a backlog of more than 18,000 “expressions of interest” to buy some of the more than 8,000 vacant lots in the city’s inventory. Many of the queries had gone unanwered for years.

Under the new system, buyers may submit formal applications for lots approved for sale as side yards or community gardens–as long as the applicant meets certain terms and conditions. The city is supposed to respond within 120 days–with approval by no means guaranteed.

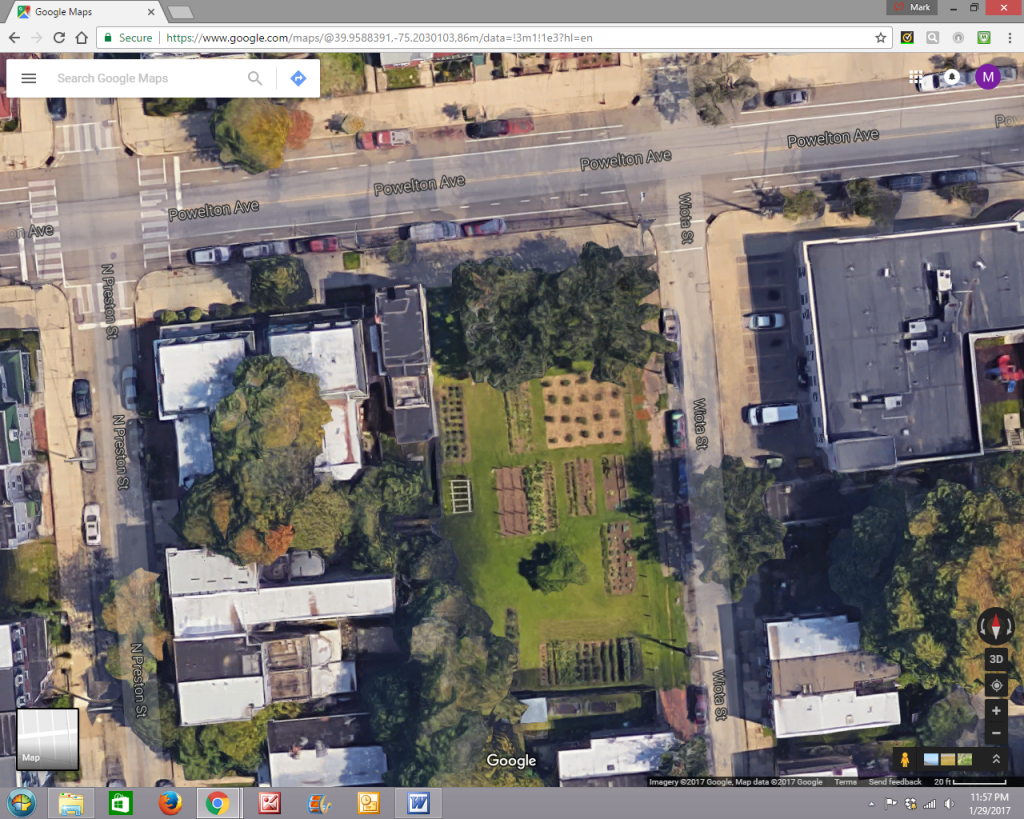

The new website acknowledges that the city has some fences to mend with community gardening advocates who have long complained about the inability to make use of blighted lots:

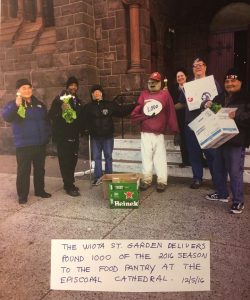

“The City of Philadelphia and PHDC have a strong commitment to community gardening and urban agriculture. Gardening is an important part in helping to transform and sustain communities. In the last five years, PHDC has done a lot of work in community gardening and urban agriculture. There is more work to do, but we are committed!”

PHDC also acknowledges that some gardens have already been established without authorization on vacant lots. The new system promises a possible path toward legalization for at least some of them:

“If you are already gardening on a lot but don’t have an agreement to do so, we may be able to formalize your garden.”

In considering applications, PHDC apparently will take steps to assure that vacant lots ostensibly purchased for use as “community gardens” aren’t commandeered for purely private use or perhaps flipped to a developer for a fat profit. That sort of scam does indeed happen with disposition of city-owned vacant lots, as WHYY and others have reported in, among others, a piece about a city judge who acquired lots for a pittance and sold them to a developer a year later for a $135,000 profit, and another article about how political favoritism can distort the process of disposing of vacant lots.

The new application process suggests the city will require proof that a purchaser has the intent and wherewithal to create and manage a garden that is actually open to the community. As the PHDC’s new website states:

The application to use property for a community garden, open space or recreational area will ask for information about you and, if applicable, your organization. It will also help us make sure you are up to date on your taxes, have no conflicts of interest, and comply with the City’s campaign contribution guidelines.

- The application also asks you to submit:

- An economic opportunity and inclusion plan

- Detailed plans

- Documentation that you have successfully completed such developments in the past

- Proof that you have the funds needed to complete the development

- Organizational documents