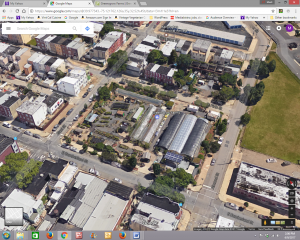

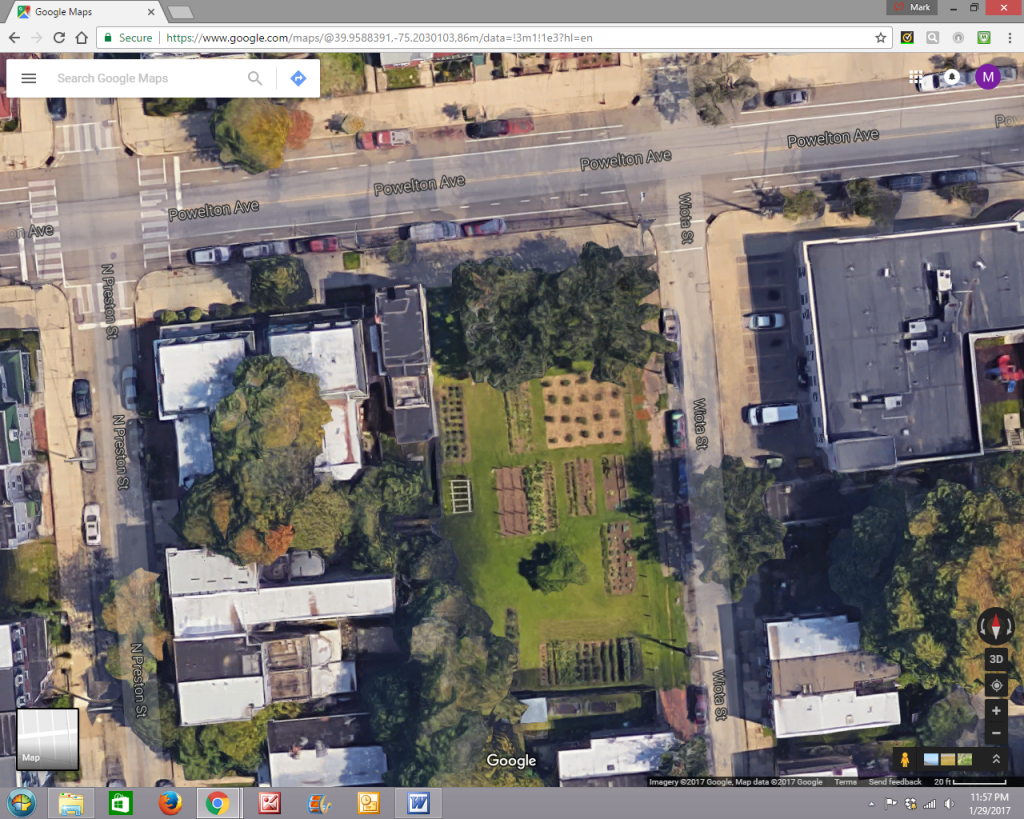

Backers of the imperiled community garden that has occupied and beautified a quarter-acre vacant lot at the corner of Powelton Avenue and Wiota Street in West Philadelphia since 1984, seem to be hoping they’ll be getting some good news soon. That would be a switch from the ominous tidings that have hovered over the Wiota Street Garden since last fall. Reports at the time indicated that a housing developer had offered between $200,000 and $300,000 for the lot, which is owned by the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority. A decision about whether to accept the deal was said to be on the desk of the local entrenched city councilmember, Jannie Blackwell, who is apparently not a big fan of the garden—nor it of her (judging from the protest signs calling her out by name that the garden posted late last year).

Google Earth view of Wiota Street Garden

Google Earth view of Wiota Street GardenPresumably the land could be sold out from beneath the garden, bringing its 33-year run to an end, any day now. But wait! A cryptic message posted on the Wiota Street Garden’s Facebook page hints there may be a glimmer of hope. It is a heavily veiled hint, to be sure, consisting of really nothing more than an exclamation point. Appended to the sentence about the unnamed new developers, it suggests they may be white knights who will save the garden.

Here’s the statement in its entirety, from the garden’s Facebook page.

“There will be a hearing at 1234 Market Street at 4pm on March 8: another set of possible developers! Stay tuned for more info.”

While awaiting further word on that, here’s a recap of some of the local press coverage from recent months about the Wiota Street Garden and its place in the now-thriving Powelton neighborhood.

Mike Lyons, a reporter for the West Philly Local, found that not all of the neighbors are wildly enthused about the garden when he attended a public hearing about it in November, with Blackwell presiding. It drew 60 people and was “divisive” at times, Lyons reported. The headline on his story summed up the outcome: Tenuous community consensus reached on preserving Wiota Street Garden.

One grievance seems to revolve around the fact that while it is called a “community garden,” it has been mostly run by one man, John Lindsay, since its inception. As Curtis Seward, who lives across the street from the plot, put it at the hearing, “John has done a herculean job keeping it up, but I don’t see any community in this so-called community garden.” That clearly resonated with Blackwell: “I hear you loud and clear,” she said.

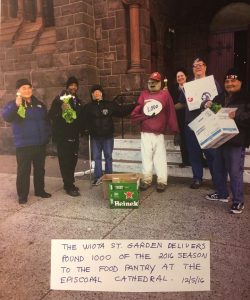

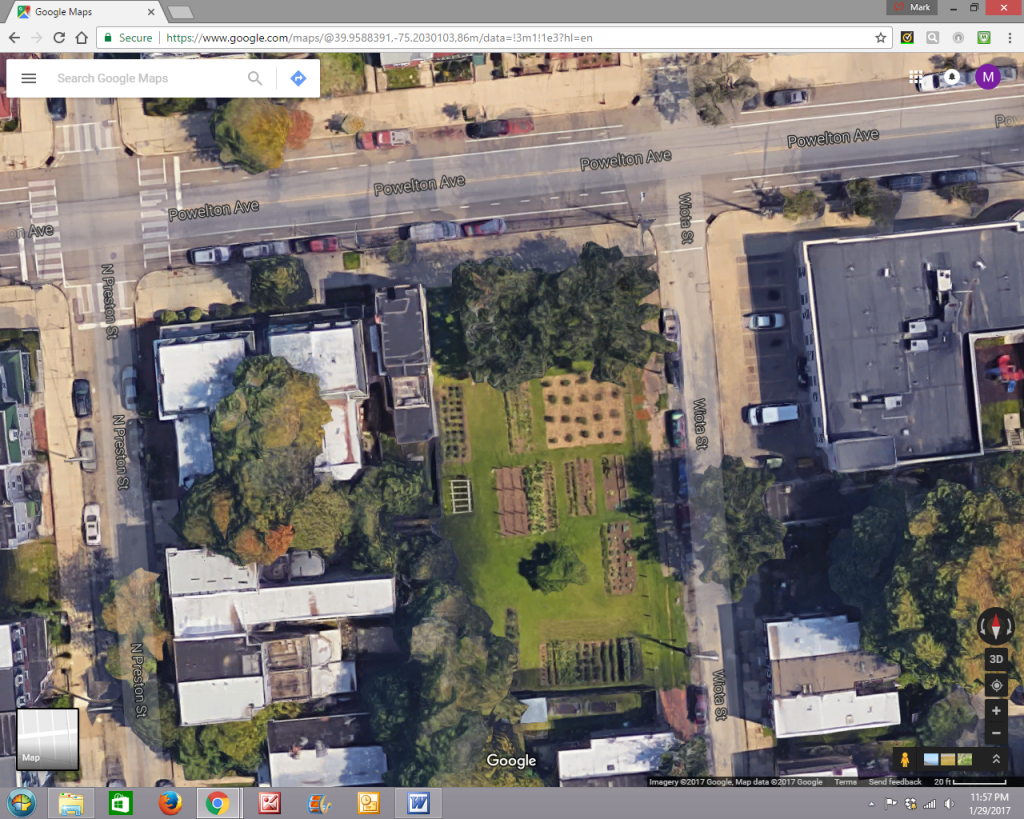

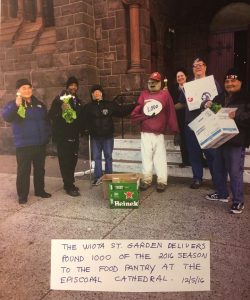

Wiota Street Garden delivers 1,000th pound of produce to food pantry (from garden’s Facebook page).

Wiota Street Garden delivers 1,000th pound of produce to food pantry (from garden’s Facebook page).A report by Nicole Contosta published i n the University City Review in January lauded the efforts made by the garden to forge new ties with the community, and to spread the news of all the good it does. The garden announced with fanfair in mid-December that it had just donated its 1,000th pound of produce for the year to a local food pantry. That followed a major honor earned by the garden in November. In its annual ranking of community gardens in Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society gave the garden a Blue Ribbon Greening Award in the Urban Farms category. Contosta goes on to say:

“This represents only a fraction of the garden’s contribution to their West Powelton neighborhood and beyond. Recently, it sponsored a neighborhood clean-up at Barring and Wiota Streets. It added a library pick up and drop off box at its perimeter. Wiota Street Gardeners collected a huge quantity of leaves that they then blended into the garden’s soil last fall. Through the PHA, it has sponsored a winter garden contest to judge the condition of gardens in the off season. And gardeners took over the maintenance of the playground at Budd and Powelton Streets.”

Inga Saffron, the Philadelphia Inquirer‘s architecture critic, covered the Wiota Street garden in one of her Changing Skyline columns in October. For failing to make a decision, or answer questions about where she stands, Blackwell is the titular villain in Saffon’s piece, “Autocratic Leadership vs. Community Gardens. But she acknowledges that the “story is a bit more complex” than its backers suggest. To wit:

“There are some 400 community gardens in Philadelphia, a legacy of the long decades of decay and abandonment. The folks who stuck it out here laid claim to whatever vacant land they could, with little concern for the name on the deed. Officials were only too happy to see orderly rows of vegetables rather than have the earth swallow up the city.

“But that was then. Philadelphia is now undergoing a rowhouse boom the likes of which it hasn’t seen since immigrants were pouring off the docks in the early 20th century. As developers scramble for any available site where they can throw up a few houses, community gardens, lovingly tended for decades, have become easy targets. At least a half-dozen are under threat of being bulldozed, including one of the oldest, the Eastwick Community Garden.”

Good luck being one that is saved from legal limbo. Amy Laura Cahn, a lawyer who serves on the board of the The Neighborhood Gardens Trust tells Saffron that of the 318 gardens that have applied for legal status from the city’s landholding agencies, only 17 have had their standing clarified in the last two years.

A year ago, Lindsay reportedly saw the handwriting on the wall and suggested that the garden trust should assume formal control of the Wiota Street Garden to preserve it as green space, keeping it safe from developers. Saffron reported that the trust was “thrilled” by the suggeston. But in order for that tyo happen, ownership would need to be turned over to trust, which would move it off the Redevelopment Authority’s books and preserve it as green space. The Trust’s executive director, Jenny Greenberg, said at the meeting that the organization’s board has approved acquisition of the plot “contingent on broad access to the garden.”

Grumblethorpe, at 5267 Germantown Ave. (see photo on left), was built in 1744 for the family of John Wister, a Philadelphia wine merchant. It was a commercial farm supplying fruits and vegetables to the Philadelphia market for a couple hundred years. Two acres of gardens remain, producing vegetables for sale at a farm stand open every Saturday from late May into October. But it primarily serves educational purposes these days through summer programs and relationships with neighborhood schools.

Grumblethorpe, at 5267 Germantown Ave. (see photo on left), was built in 1744 for the family of John Wister, a Philadelphia wine merchant. It was a commercial farm supplying fruits and vegetables to the Philadelphia market for a couple hundred years. Two acres of gardens remain, producing vegetables for sale at a farm stand open every Saturday from late May into October. But it primarily serves educational purposes these days through summer programs and relationships with neighborhood schools.